Table of Contents

Introduction 1

Key Concepts 2

Metadata 5

Electronic Mail 8

Electronic Records Transfer 11

Personal Devices 13

Social Media 14

Trusted System 15

Digital Signature 16

Electronic Data Management System 18

Digital Imaging/Scanning 21

Appendix A: Glossary 24

Introduction

Records managers, in tandem with their day-to-day responsibilities, must be aware of emerging

technologies and the impact they may have on their RIM program. As agencies begin to adopt more and

more new technologies, records managers must begin to prepare for how to properly manage these

records and information.

The California Records and Information Management Program (CalRIM), along with other Archives staff,

has created this Practical Guidebook for Managing Electronic Records to assist state agencies in

developing of appropriate strategies and management practices for electronic records. This guide is

intended to be a starting point to assist state agencies so that informed decisions are made regarding

the electronic component of an agency’s records management program. This guide should work in

conjunction with CalRIM’s Records Management Handbook to direct the user to best records

management practices.

Our ability to manage and control records has not kept pace with our ability to create records and

today’s highly technical environment means that more records will be created and stored electronically.

Records managers, in addition with their day-to-day responsibilities, must be aware of emerging

technologies and the impact they may have on their records management program. Maintaining

complex records such as data spreadsheets, geospatial files, and digital video, requires a different

approach to ensure that the files are readable throughout their retention period. As agencies adopt

more new technologies, records managers must prepare to properly manage these records and

information.

A firm understanding of electronic records management is becoming crucial for records managers in

today’s digital environment. This guidebook will assist those seeking information on topics that are

most pertinent for records managers today including email, metadata, trusted system and more. The

goal of the guidebook is to equip users with information that will help foster informed decision making

for an agency’s records management program.

10/20/2015 1

KEY CONCEPTS

An understanding of the following key concepts is helpful for the development of an agency’s electronic

records management program.

• Definition of a Record

• Electronic Records

• Information Governance

• Metadata

• Long-term Retention Approaches

• Electronic Records Management Goals

Definition of a Record

The California Public Records Act (CPRA) defines a public record as, “any writing containing information

relating to the conduct of the public’s business prepared, owned, used, or retained by any state or local

agency regardless of physical form or characteristics.”

1

A record includes all forms of recorded

information that currently exist or that may exist in the future. The CPRA specifies a record as any,

“handwriting, typewriting, printing, photostating, photographing, photocopying, transmitting by

electronic mail or facsimile, and every other means of recording upon any tangible thing any form of

communication or representation, including letters, words, pictures, sounds, or symbols, or

combinations thereof, and any record thereby created, regardless of the manner in which the record has

been stored.”

2

Essentially, an official state record includes any and all information produced for the purposes of

conducting government business regardless of the format the record might take.

Electronic Records

Various types and formats of electronic records exist but there are two main categories of electronic

records: born digital records and digitized records. Born digital records are those records created with a

computer that require a computer to be readable by people. A digitized record is one that is born

analog (paper) and has been converted into a machine readable format using a scanner or camera. For

the purposes of this handbook electronic records of both types should be handled in the same way.

Electronic records such as email and word processing documents may resemble analog records, but

more sophisticated electronic records such as geospatial records and databases exist which do not bear

resemblance to analog records.

No matter how the electronic record was created, it is important to remember that an electronic record

is one that requires a computer to read and translate the information for people to read.

1

California Public Records Act, Government Code Section 6252(e).

10/20/2015 2

2

California Public Records Act, Government Code Section 6252(f).

Information Governance

The idea of information governance can be attributed to the explosion of electronic data generated in

recent decades. In short, information governance may be interpreted as records management for

electronic records. Information governance incorporates additional records management

methodologies which cater to the unique issues records managers face when dealing with electronic

records. Some of the fundamental principles of information governance such as appraisal, use, storage

and disposition will resonate with records managers versed in analog records but proper management

of electronic records necessitates attention to issues such as metadata management, storage

optimization, electronic discovery requirements, and privacy attributes that may prove foreign to some.

Appropriate information governance is crucial to the support of an agency’s immediate and future legal

requirements regarding electronic records.

Information governance establishes a course of action for electronic records to ensure their appropriate

and effective use and to allow an agency to meet its specific goals.

Metadata

Metadata plays a central role in electronic records management. Often defined as “data about data,”

metadata’s function is essential for e-discovery and determining record authenticity. Specifically,

metadata describes the content of a file and allows users to locate and evaluate data. Metadata is most

useful if a structured format is in place using a controlled vocabulary.

For a more thorough overview of metadata please see the “Metadata” section of the handbook.

Long-Term Retention Approaches

Given the variety of digital records and the fast pace of changing technology one must consider options

for ensuring access to records that an agency may want to retain for future use.

• Conversion. Converting a file such as a word document into a platform neutral format greatly

increases the chances of having the file available for future use. One option may be to convert

files retained for future use into PDF/A. Given the availability of programs such as Adobe

Acrobat which easily convert files into a more desirable PDF/A format this approach is feasible.

A records manager may want to inform or educate staff about converting files that may be

needed by the agency for future use.

• Migration. Migration refers to moving a record or file from one platform, storage medium, or

other physical format to another. For example, an agency may have active records that are

stored on volatile magnetic disks. Migrating those records to more stable storage such as a

storage server or optical disc is imperative to ensure availability for future use.

The needs of an agency and the electronic records that are identified as worth retaining will dictate

strategies for long term records retention. Given the complexities of electronic records it is best to

10/20/2015 3

consult with your agency’s information technology department on a solution that promotes long term

availability of active electronic records.

Electronic Records Management Goals

Electronic records management requires planning, budgeting, organizing, directing, training, and the

control of activities associated with managing records. Electronic records require continuous

management throughout their entire lifecycle because of the potential for lost or unreadable data. This

is a complex task amidst the ever growing volume and diversity of electronic information. Whatever the

methodical approach taken by your agency for your electronic records program, some key records

attributes to be aware of include the following:

• Trustworthy. This refers to the information that is retained in your records. Is it reliable,

authentic, and unaltered? Will your records hold up in a court of law if necessary? A

collaborative effort with your IT department to identify and implement a strategy to ensure

authenticity and trustworthiness of your records may prove valuable if the records in question

go before a judge.

• Complete. Is the information contained in your records stored in such a way that it will be

comprehensible if needed in the future? Proper metadata input will help identify the records’

relationship to that of the agency’s activity and to other records. Metadata is also helpful in

discovering the record for future use. A record is not complete if it cannot be located and used

at a later time.

• Accessible. If your record is not accessible it is useless. Therefore a strategy to locate and

access records is important. Whether the records need immediate access or not can be

determined by the needs of your agency and the possible public interest in the record.

• Durable. Again, if your record is not readable it is useless. Safeguarding records against

possible loss is key to the records’ durability and should be considered when selecting how and

where to store them. The lifespan of storage media is not very long. The fast pace of changing

technology may make it impossible to read files off of certain storage media after less than ten

years. One should also consider the environmental conditions of where the storage media will

be held. A hot warehouse or damp storage container are not ideal holding areas for any

storage media. Electronic records to best in climate controlled conditions.

10/20/2015 4

Metadata

Summary

Metadata, sometimes referred to as “data about data,” is the additional descriptive information about

digital content that makes records useful, meaningful, and findable. Beyond resource discovery,

metadata is used to describe the character or content of a digital object such as page number order,

technical aspects like image resolution, and is also used to ensure continued access to a digital object.

Maintaining and updating metadata for an agency’s electronic resources provides benefits such as easier

and more efficient discovery of relevant information. Not only does metadata facilitate resource

discovery within an agency but it can help organize and manage electronic resources when the

inevitable system backup, restoration, or migration takes place at an agency.

Metadata Categories and Functions

There are several types of metadata to keep in mind. They will all prove useful in maintaining the

content, context, and structure of your records and in keeping them useful and available for the long-

term.

• Descriptive Metadata – Describes a resource for the purpose of indexing, discovery, and

identification. Common descriptive metadata fields include creator, title, and subject.

• Administrative Metadata – Helps manage a resource by describing management information

such as ownership and rights management.

• Structural Metadata – Used to display and navigate digital resources and describes relationships

between multiple digital files, such as page order in a digitized book.

• Technical Metadata – Describes the features of the digital file, such as resolution, pixel

dimension, and creating hardware. The information is critical for migration and long-term

sustainability of the digital resource.

• Preservation Metadata – Contains the information needed to preserve a digital object and

protect the object from harm, deterioration, or destruction. Preservation metadata may

encompass the aforementioned forms of metadata.

One of the most pressing reasons an agency will want to create descriptive metadata is to ensure the

discovery of information. If an agency receives a request by the public for information concerning the

business of the state, high quality descriptive metadata will make the search and retrieval of an

electronic resource relating to the request much more manageable. An electronic resource with high

quality metadata allows the user to identify resources, distinguish relationships with other objects, bring

similar resources together, and determine location information.

There are many compelling reasons for recording metadata but, in terms of support for government

agencies, metadata is useful for:

1

0/20/2015 5

• Legal and statutory requirements

3

• Advancements in technology (upgrading servers)

• Providing service to citizens and other agencies (identifying , locating, and sharing information)

• Optimal workflow (easily finding documents and understanding their context)

• Operational, administrative and preservation needs (Decision making documentation)

Where Does Metadata Live?

To better understand metadata it is important to know where the information or metadata is stored.

Metadata can be embedded within a file. For example, when an image is scanned the associated

metadata such as file type, date scanned, file name, and image resolution lives with the file or is

embedded in the file.

A file’s metadata does not necessarily have to live within the file. An external catalog of metadata for an

agency’s files can provide an efficient avenue for managing and discovering files at a later date. Utilizing

a data spreadsheet such as Microsoft Excel or Access allows a user to tailor metadata entries that best

suit the needs of the agency. Best practice dictates that two datasheets be maintained when practicing

the catalog method for recording metadata: a master copy with permissions granted to select users and

a use copy that allows access to all individuals who may need to use the data to perform work duties. A

metadata catalog is an efficient way to manage electronic resources and boasts advantages such as:

• Offline searching

• Collection-wide searching

• Providing a record of an agency’s electronic records.

Metadata Schemas and Element Sets

Many different metadata standards, or schemas, exist for a variety of users and disciplines. One of the

most common metadata schemas, Dublin Core, is versatile and easily applied to an assortment of

objects from many different professions and disciplines

4

. The Dublin Core schema consists of fifteen

elements: Title, Creator, Subject, Description, Publisher, Contributor, Date, Type, Format, Identifier,

Source, Language, Relation, Coverage, and Rights. Design to be simple and concise, the Dublin Core

schema is able to accommodate the increasing presence of electronic resources.

When using a metadata schema it is also important to exercise a controlled vocabulary. A controlled

vocabulary consists of an approved set of terms for the content of the elements. For example, there is

more than one way to write a date so it is important to set forth an approved method (i.e. 02_02_2005

or February 2, 2015). The format for proper nouns should also be agreed upon (e.g. Smith, Joan or Joan

Smith).

3

California Public Records Act, Government Code Sections 6250-6276.48 Government Code 6252 (e); California

State Records Management Act, Government Code Sections 12270-12279 Government Code 12275 (a)

4

The Dublin Core Metadata Element Set is a set of guidelines for cross-domain resource description. ISO

15836:2009

10/20/2015 6

Ultimately an agency must decide on what metadata schema will work best for them, however

employing a high quality standard will ensure consistency across an agency’s files and allow objects to

be found and compared more easily.

File Naming Conventions

A file name is the key identifier of a digital object and provides metadata for the record. Consistent and

descriptive file names will provide a more organized and easily understood collection of records. How a

file is named will have a large impact on finding the files at a later date and understanding their

contents. The following information might be considered when creating a file naming policy although

ultimately file names should reflect the purpose and need of an agency:

•

•

•

Project name

Date or date range of

creation

Version number

•

•

•

Name of intended

audience

Description of content

Department

•

•

•

•

Publication date

Release date

Record series

Name of creator

When creating a file naming policy the following should also be considered:

• Create unique file names.

• File names should be easy to understand and not overly complex.

• Do not use spaces but rather (_) or (-) to represent a space.

• Avoid using special characters such as $ # @ & ^ % * ! and use only alpha-numeric characters.

• Limit file names to 25 characters or less.

• Use the three character file extension with a period (e.g. .tif not .tiff) at the end of the name.

• Don’t rely on the system to differentiate between upper and lower case and be consistent in

what is used.

• If digits are included in the file name, include the appropriate amount of leading zeros and be

generous so your project can be scalable.

• It’s helpful to include metadata in the file name but this can be cumbersome if you have huge

numbers of files. That said, consider using shortened versions of 1) a standardized date, 2)

version number (only if this can/will vary), 3) creator’s name, and 4) description/type of

document/subject in the file name and in a logical order.

• Document whatever naming convention is settled on. This really is the key. Include the naming

convention document any time records are transferred elsewhere.

10/20/2015 7

Email Management

Electronic mail, more commonly known as email, is routinely used by state agencies. Email is often used

as the mode of communication for brief messages that were once relayed by telephone and to

disseminate substantive information previously committed to paper sent by more traditional methods.

This combination of communication and record creation/keeping has caused ambiguity in the record

status of e-mail messages.

The California Public Records Act (CPRA) defines a public record as, “any writing containing information

relating to the conduct of the public’s business prepared, owned, used, or retained by any state or local

agency regardless of physical form or characteristics.”

5

The CPRA thus applies to email messages and

requires that proper identification and care of email be performed by the agency. An agency’s records

management policy must address email messages to ensure record emails are properly identified and

managed.

Retention and Disposition of Email

Email is not considered a record series or category on its own. It is simply a format. Retention or

disposition of an email messages is done in relation to the information they contain, the purpose they

serve, and the relevant line item/records series to which it belongs. Given the frequent use of email, it

should be evaluated on a regular basis with transitory emails being deleted when no longer needed. The

content of an email message determines whether the message is a record.

The content of email messages may vary considerably and, therefore, must be evaluated on a case-by-

case basis to determine the length of time the message must be retained. Email that provides insight

into the organization and functions of an agency and contains content with historical value must be

“filed,” just as you would a paper record, in an e-folder with similar business or program items. Record

emails may be flagged for transfer to the State Archives at the end of their retention period. An agency

must have an email management policy in place to ensure record emails are not deleted alongside

transitory emails. A policy should outline a routine for ensuring record emails are properly identified

and saved.

5

California Public Records Act, Government Code Sections 6250-6276.48 Government Code 6252 (e).

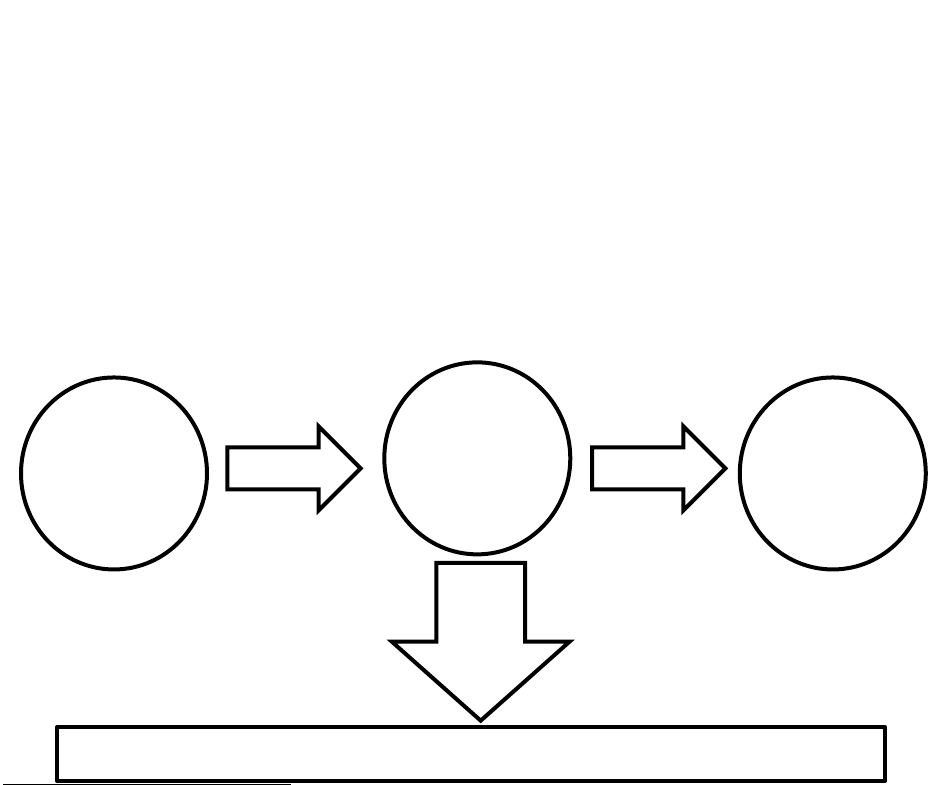

Email

Received/

Sent

Is it

Agency

Business?

Delete

After No

Longer

Needed

If “No”

If

“Yes”

Determine Record Series/Line Item of Email and File According to Retention Schedule

10/20/2015 8

Determining Value of Email

Based on CPRA’s definition, email messages containing subject matter such as policies and directives,

final reports, and meeting minutes are identified as record emails. Transitory and personal emails that

do not provide insight into government business such as an email regarding a lunch meeting time should

be deleted after they are no longer needed.

Remember that the transactional information (metadata regarding sender, recipient, time sent,

and similar) associated with each message, and any attachments to the body of the message are

all part of an email message. This means that a printout of an email may not be satisfactory as a

record.

Email that are classified as official records are subject to the individual department’s records retention

schedules and must be retained for the same period of time as the record retention line item/records

series that most closely matches the subject matter contained within the email. If there is no entry that

resembles or matches the subject matter of the message, the “record” should be added to the

appropriate retention schedule as a separate series of records.

Transitory e-mail consists of electronic messages that are created primarily for the communication of

informal information as opposed to the perpetuation or formalization of knowledge. Destroy transitory

email when it has served its purpose.

Email Policies

An agency’s email policy should be developed to enhance management of record emails. An effective

policy includes direction on topics such as email filing methods, email subject lines, and storage and

retention of email, thereby increasing the accessibility of records. Policies should include whether the

sender or the receiver should save email records, how to determine if an email is a record, and how to

segregate record email into the appropriate series and record storage. Non-record and duplicate emails

should be deleted from mailboxes regularly. If an agency receives a request for an email record for a

litigation issue, for example, a well-planned email policy can help ensure that the record is discoverable

during its retention period or show that its deletion was properly carried out according to retention

policy.

S

ubject lines are helpful for both the recipient and sender in identifying and filing messages. They are

also crucial for efficient email records discovery. Subject lines should be unambiguous and as

descriptive as possible so that records are more accessible and searchable.

Poor or confusing subject lines:

“Helpful Info”

“Report”

“Minutes”

“Important”

“News”

“Contract Status”

Better, descriptive subject lines:

“Contact Info”

“Quarterly Financial Report”

“January 2001 Board Minutes”

“Revised Administrative Procedures”

“New Agency Head Appointed”

“PO 12345 Delivery Status”

10/20/2015 9

Individuals should configure their email filing to ensure accessibility to email records. Email systems

should be configured so that email messages can be indexed in an organized and consistent pattern

reflecting the ways in which records are used and referenced.

1

0/20/2015 10

Transferring Electronic Records

to the California State Archives

Electronic records are bound by the same legal requirements as paper documents. An agency’s

retention schedule should reflect any electronic records produced by the agency, and they should

undergo the same evaluations as paper documents for retention and disposition. As part of the schedule

review by CalRIM and SRAP electronic records bearing administrative, legal, and historical value may be

“flagged” for transfer to the Archives. At the end of their retention period flagged records must be

transferred to the State Archives, in accordance with California state law:

“A record shall not be destroyed or otherwise disposed of by an agency of the state, unless it is

determined by the Secretary of State that the record has no further administrative, legal, or

fiscal value and the Secretary of State has determined that the record is inappropriate for

preservation in the State Archives.”

6

Electronic records come in a variety of formats and record types and may include textual data (word

processed, formatted, and unformatted or (plain) text), structured data (databases, spreadsheets),

email, computer-aided design (CAD) files, digital audio, digital moving images, digital still images,

geospatial data, presentation files, and web records. Because of this variety, electronic records require

special considerations prior to transfer.

Preparing Electronic Records for Transfer

A successful electronic records transfer requires the coordination of the agency’s records managers and

IT, and the staff at the State Archives. When transferring electronic records, the following should be

considered and discussed with the parties involved to ensure an effective records transfer:

• Have records reached the end of their retention period?

• Are record series appropriately identified?

• Have the file formats been identified?

• What is the number of records being transferred?

• What is the volume of the records? (in terabytes, gigabytes)

• Do any access restrictions apply to the records?

• What metadata is included with the records?

• Have files been vetted for encryption and, if any encrypted files exist, is there a means of

decryption transmitted with the file?

• What is the method for transmission? (A secure File Transfer Protocol or portable device?)

6

California State Records Management Act, Government Code Sections 12270-12279 Government Code 12275(a).

10/20/2015 11

File Formats for Transfer

Some file formats are more desirable for long-term preservation than others. For example, a Microsoft

Word document is more vulnerable to obsolescence than a PDF/A file and is not ideal for ensuring long-

term access. Consulting with your IT department and staff at the State Archives can help establish the

appropriate format for files pending transfer.

10/20/2015 12

Personal Digital Devices

Given the prevalence of portable digital devices, it is no surprise that many employees are using their

own personal devices to perform state work. This practice is often referred to as Bring Your Own Device

or BYOD. BYOD raises many issues and concerns for records management practices and is not the easy,

cost effective solution that some agencies may consider it to be.

Data Management

A BYOD policy makes it difficult-to-impossible to ensure that proper information practices are being

followed by the operator of the device. If an agency finds itself in a lawsuit, an auditor will want to

know what steps the agency took to ensure that the data in question was adequately protected on an

employee’s personal device.

Security

There is always concern about security when it comes to personal devices.

• Lost or Stolen Devices – One potential security issue that arises with the use of BYOD is the

potential for employees to lose their personal devices containing unsecured data. Depending on

the scope of work of the employee or the agency involved, sensitive information may land in the

wrong hands.

• Malware – There is always the potential for an application downloaded to a portable device to

contain malicious software that may compromise the device in use and any information

contained on it.

• Disgruntled employees – Unfortunately, not all employees leave an agency on good terms and,

if disgruntled employees have sensitive information on their personal devices, they may choose

to publish or disseminate information not meant for the public.

Privacy

One concern an employee should have with a BYOD plan is the potential for a breach in their privacy. If

information on a personal device is needed for legal reasons, a search of the device will not only yield

the state records but also any personal records such as email that may be on the device. All the

information on the device would have to be preserved for discovery purposes and a “wipe” or complete

erasure of data would not be possible because of the legal obligations involved with state records.

An agency with a BYOD policy is potentially opening a Pandora’s Box of legal and privacy issues. If a

portable device or laptop computer is needed for an employee to complete essential job duties, best

practice would be to issue a state owned device that has the proper IT support to accommodate security

and discovery issues.

10/20/2015 13

Social Media

Social media is a broad term that incorporates various web based technologies such as blogging, video

sharing, wikis, social networks, and photo libraries. Most state agencies operate one or more social

media accounts which has added another dimension to records management.

Social Media Records

Social media provides another avenue for agencies to engage with the public and to collaborate

internally. One of the challenges presented by social media is the identification of a record. An entry on

a social media site might not always constitute a record. The following should be considered when

trying to determine if an entry on a social media site is a record:

•

•

•

•

•

Does the social media content contain information or evidence concerning an agency’s mission

or policies?

Is the information unique or available elsewhere?

Does the social media content contain evidence of official agency business?

Does it document a controversial issue?

Does it document a program or project that involves prominent people, places or an event?

If the answer to one or more of the above questions is yes, then the social media entry is a record.

Unless the content created in social media denotes a new record series, social media records will most

likely fit in the characterization of an existing record series such as press releases. If the social media

records indeed represent a new records series, the RRS should be updated to reflect the new series.

URLs for sites or for feeds can be included in the remarks column of the records retention schedule. The

State Archives will then have the opportunity to flag any appropriate social media for eventual transfer

to the Archives. If social media records are flagged for archival values, the State Archives request that

the state agency preserve and then transfer files at the end of the retention period. If social media

records are not flagged for transfer to the State Archives, the agency can then destroy social media

records upon the end of their retention period.

If, in fact, a social media entry is considered a record that must adhere to a retention schedule, the issue

of how to capture the record arises. Social media records may prove a little more complex than

traditional electronic records given their ability to allow enhancement with additional comments,

metadata, or other information. A plan to export records from a social media site to a recordkeeping

system is important and should be created in collaboration with an agency’s IT department. There are

web crawling tools and software to capture social media entries but these may prove cost prohibitive for

an agency. Storing the original content, such as a video, elsewhere beyond the social media site may

suffice for ensuring retention of a record. An agency could also keep a file of blogs and social media

entries, which would at least ensure that the original content would be retained.

10/20/2015 14

Trusted System

In 2012, California adopted regulations that require state agencies to employee a trusted system for

maintaining all electronic records created or stored as an official record. The State of California defines

a trusted system as, “a combination of techniques, policies, and procedures for which there is no

plausible scenario in which a document retrieved from or reproduced by the system could differ

substantially from the document that is originally stored.”

7

The aforementioned is achieved through a

combination of incorporated technology and documented procedures regarding the plan, development

and execution of the system.

Why a Trusted System?

Agencies that wish to destroy paper documents and rely solely on electronic versions will need a

trusted system in place. A trusted system certifies that electronically stored information (ESI) is an

authentic copy of the original document or information. An agency may choose to eliminate paper due

to lack of storage space and improve speed and efficiency of processing documents with faster access

based on electronic versions of documents.

Given the relative ease one can manipulate an electronic record, a trusted system is crucial for ensuring

official records are non-alterable. At the minimum, an agency has a responsibility to ensure that their

records are safe and secure, but litigation issues should also be considered. Electronic documents

presented in a court of law will need to be proven as authentic to serve as evidence.

What is Required of a Trusted System?

A trusted system must include an avenue for maintaining at least two separate copies of an electronic

resource. A combination of proper hardware and media storage techniques are necessary to prevent

any unauthorized additions, modifications, or deletions to a document. A trusted system must also

stand up to the rigors of an independent audit process that ensures that no plausible scenario for

altering documents is feasible. Lastly, a trusted system requires that at least one copy of a stored

electronic document or record is written that does not permit any unauthorized alterations or deletions

and is stored and preserved in a separate and safe location.

Achieving a Trusted System

The task of establishing a trusted system is one that should not rest solely on an agency’s records

manager. Establishing a trusted system requires support from an agency’s management and

information technology department. The task requires the involvement of many parties because a

trusted system is not simply putting the proper technology in place but also requires an organization to

document policies and procedures that provide for proper electronic record handling and processing.

7

CA Government Code 12168.7 (c)

10/20/2015 15

Digital Signatures

Digital signatures provide a means to authenticate an electronic document. In other words, they

identify the original creator of the document and that the document has not been altered since its

creation. In addition, a digital signature can serve as evidence during litigation, demonstrating that an

electronic document came from the claimed signatory. A digital signature is a mechanism designed to

provide a document with integrity, authenticity, and security. Any changes made to the document after

the digital signature has been applied visibly void its authenticity.

The Uniform Electronic Transaction Act (UETA) defines an electronic signature as “an electronic sound,

symbol, or process attached to or logically associated with an electronic record and executed or adopted

by a person with the intent to sign the electronic record.”

8

Many agencies provide services that require

transmission of electronic documents. With paper records, a “wet signature” certifies that the content

of a document is authentic. A valid digital signature can be thought of as the electronic equivalent of

the analog “wet signature.”

Purpose of Digital Signatures

The American Bar Association identifies the following as the general purposes for signatures:

•

•

•

•

Evidence: A signature authenticates a record by identifying the signer with the signed

document. When the signer makes a mark in a distinctive manner, the writing becomes

attributable to the signer.

Ceremony: The act of signing a document calls to the signer’s attention the legal significance of

the act and helps prevent inattention or inappropriate approval.

Approval: In certain contexts, a signature expresses the signer’s approval or authorization of the

record or the signer’s intention that it have legal effect.

Efficiency: A signature on a written document often imparts a sense of clarity and finality to the

transaction, and may lessen the subsequent need to inquire beyond the face of a document.

9

How Does a Digital Signature Work?

A digital signature authenticates an electronic document by utilizing certain types of encryption.

Encryption is the process of encoding the information of the electronic document in a way that requires

a key or password in order for the recipient to read the information.

8

California Civil Code Section 1633.2(h)

9

American Bar Association. Digital Signature Guidelines Tutorial. Section of Science and Technology Information

Security Committee.

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/events/science_technology/2013/dsg_tutorial.authcheckdam.pdf

10/20/2015 16

Using Digital Signatures

The method an agency employs for a digital signature must be created by a technology that is

acceptable for use by the State of California.

10

Agencies interested in developing a plan that involves

digital signatures should consult with their agency’s IT and legal departments in order to identify the

best solution. A digital signature must adhere to the following criteria to ensure the technology is

acceptable for use by public entities:

•

•

•

•

•

It is unique to the person using it.

It is capable of verification.

It is under the sole control of the person using it.

It is linked to data in such a manner that if the data are changed, the digital signature is

invalidated.

It conforms to Title 2, Division 7, Chapter 10 22001 of the California Code of Regulations.

10

Approved List of Digital Signature Certification Authorites,

http://www.sos.ca.gov/administration/regulations/current-r

egulations/technology/digital-signatures/approved-

certification-authorities

10/20/2015 17

Electronic Data Management System (EDMS)

An Electronic Document Management System (EDMS) is a software package designed to manage

electronic information and records within an organization’s workflow. Utilizing various technologies, an

EDMS allows a user to manage the creation, storage, and control of records. An EDMS can automate

processes and increase efficiency. Before adopting an EDMS, it is necessary to determine how it will fit

in with your agency’s records management program. It is not a replacement for sound records

management practices.

Functions of an EDMS

Many different EDMS systems exist. Each provides various functions tailored to specific and unique

needs, but all EDMS systems should include the following basic functions:

•

•

•

S

ecurity Control – This feature is crucial to control access to information. A system should have

a mechanism to safeguard documents that are exempt from disclosure and allow access to

those records which should be made publicly available.

Addition, Designation, and Version Control – The EDMS should allow users to add documents to

the system and designate a document as an original government record. It should also

automatically assign the correct version designation.

Metadata Capture and Use – The EDMS should allow the user to capture and use the

appropriate metadata according to an agency’s needs.

Optional Functions

• Records Management – Not every EDMS is equipped with records management capabilities.

Systems with a records management component are sometimes referred to as an Electronic

Document and Records Management Systems (EDRMS).

•

•

•

Storage – An EDMS may provide storage within the EDMS or the ability to work with an adjunct

storage system.

Free-Text Search – An EDMS may allow users to search every word in an entire document while

other systems only provide metadata searching capabilities.

Automatic Conversion – This function provides the user with automatic conversion of a

document from one file format to another (e.g. from a Word document to a PDF) after the file

has been designated as a record.

Benefits of an EDMS

Most state agencies create, collect, process, distribute, store, manage, retrieve, maintain, and dispose of

enormous amounts of electronic information. An EDMS may improve efficiency and effectiveness of an

agency by:

10/20/2015 18

• Improving Access to Records and Information – An authorized user can search documents within

an EDMS and workflow can automatically notify a user when needed information has arrived or

been processed.

Improving Customer Service – Retained information can be immediately accessed by a user and

easily transmitted to a customer whether it is a member of the public or a representative from

another state agency.

Minimizing Duplication – A single copy of a document can be made available to all authorized

users. Knowing that only one copy exists is especially useful when disposing of records.

Business Process Automation – Certain processes that were once done manually may be

performed automatically by an EDMS.

Regulatory Compliance Improvement – Compliance with records retention schedules can be

automated and improved with incoming documents being automatically classified and stored by

the system.

•

•

•

•

Selecting an EDMS

When preparing to select, implement, and manage an EDMS for an agency, appropriate stakeholders

should be identified and brought to the table for discussion. Establishing and assessing the needs of an

agency should be the first order of business. Each agency will have a unique set of needs depending on

legal obligations and records management strategies, but trustworthiness, completeness, accessibility,

legal admissibility, and durability are all critical (these concepts are further explained in the “Key

Concepts” section of the guidebook.) The types of records an agency creates now, in the future, should

be considered when examining options for an EDMS along with the following questions:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

What are the current and future needs of all involved stakeholders?

How will the EDMS system be used? Solely for workflow or also for records management?

What types of records will be captured and managed using the EDMS?

Will existing records be migrated into the system?

What type of metadata should be used and who will manage it?

What records need to be shared and stored?

How will records be stored and organized to better facilitate retrieval and access? Records

should be properly filed before system implementation.

How will records be disposed of from the EDMS?

Does the system facilitate the ability to easily transfer, convert, or migrate records?

What features are most essential or desired by the agency? Are other useful but non-essential

features desired?

Will the new EDMS integrate with existing systems? (i.e. email systems, databases)

10/20/2015 19

Implementation and Deployment of an EDMS

Once an appropriate EDMS is selected, internal stakeholders and the EDMS vendor must develop a

comprehensive implementation and deployment plan. A plan will outline how and when the system will

be installed, and tested, as well as provide a background of the system. The workflow should be

documented and tested. Consider allowing eventual users of the EDMS to participate in the testing of

the system while soliciting their feedback. A training program and procedures should also be developed

before the system is fully deployed to provide users with the necessary tools to use the system to its

maximum potential. Ongoing management of the system will also be necessary.

10/20/2015 20

Digital Imaging

The decision to scan should be made by a team. Records creators, records users, records management

staff, and IT staff should all be involved. Digital imaging of records can enhance accessibility, workflow,

and productivity, but digital imaging projects can also be complex, time-consuming, and cost prohibitive.

Besides high initial costs, digital images require proper management including continuous maintenance

to ensure the records are trustworthy, complete, and durable for as long as they remain on an agency’s

records retention schedule and for the possible transfer of records to the State Archives. The operations

and needs of state agencies differ; it is important to ensure that a digitization project is adequately

staffed, affordable, and tailored to the needs of a specific agency.

11

What should be scanned is a complex question. Considerations include potential use, access, and cost.

Other concerns include record volume, preservation needs, legal restrictions, present and future storage

costs, appropriate storage formats, and whether the materials are in high demand. Before beginning

any scanning project, input should be sought from the records users, records creators, IT specialists,

records managers, and any other staff that might provide valuable input. The following are some of the

questions that should be addressed:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

W

hat are the goals for the digitization project?

What is the desired end result? A document management system? Document preservation?

Online search capabilities to facilitate better access to records?

What materials will be digitized? Textual documents, photographs, or maps? How much

material?

What resources are readily available? Scanners? Software? Expertise?

What file formats are most suitable for the agency’s requirements?

What image quality is required? Black and white? High resolution?

What condition are the documents in? Is preparation required (e.g. removing staples and

paperclips)?

What different type(s) of digital storage media will be used?

What metadata is necessary for each file? Is the metadata readily available or is time needed to

gather information?

How will access be provided to the digital records? Intranet or internet? Offline? DVD, CD, Hard

drive?

How long will the digital files be retained? If the retention schedule dictates a prolonged

retention period, what strategies for long-term document preservation must be employed? Will

hard-copy documents be kept? What is considered the original?

Do the benefits of digitization justify the cost of the project?

11

Per the National Historic Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) “a total cost of $1-$3 per scan is

reasonable for homogeneous textual collections in good condition.”

http://www.archives.gov/nhprc/announcement/digitizing-faqs.html

10/20/2015 21

Temporary Office Scans Versus Long-Term Scans

Immediate business needs often differ greatly from preservation scanning needs. Ideally, scanning

should be done once, with both immediate use and long-term preservation requirements met. Long-

term preservation, however, requires a long-term plan. For example, scans retained for preservation

purposes should be made at a high resolution with careful attention to detail. In addition, such high

resolution scans require greater storage space, greater security measures, and maintenance plans to

ensure access over a period of decades. All of these factors increase the cost of creating as well as

maintaining such scans.

Providing Access

The public expects uninterrupted access to digital materials. Luckily electronic records are easily copied

and shared. However, this benefit comes with concerns regarding the authenticity of records and must

lead to extra security precautions to ensure that the records are not altered by those accessing them.

Additionally, a digital repository requires extensive funding and ongoing maintenance. Without proper

maintenance data can be lost and recovering data that can not be read is extremely costly.

Providing access will require a plan, time, and money once the records are digitized. How will access be

provided to users? Will any specific terms or conditions be configured to allow access? Can records

nearing the end of their retention be easily identified in order to determine if they will be transferred to

the State Archives or destroyed. How will non-public content be secured? If records are to be presented

in court, they generally must be certified. Electronic records can only be certified if they reside in a

trusted system as specified in state regulations (2 CCR 22620.1-22620.8). The infrastructure required for

such a system is costly and requires long-term planning and budgeting. A major consideration for the

trusted system is that it requires the creation and maintenance of redundant copies. Redundant copies

require additional storage space, adding to the cost of such digital files.

Metadata

A well thought out scanning project must provide direction and standardized procedures for entering

metadata for scanned images to ensure uniformity with all objects involved in the digitization project.

Metadata, often referred to as “data about data,” describes the characteristics of the object and

provides meaning, context, and organization.

M

etadata is an essential component of a digital imaging project. Complete metadata will allow searches

by subject heading and keyword. The value of metadata is especially evident when documents are

requested for litigation purposes: the ability to quickly and efficiently locate documents can save an

agency time and money.

For a more thorough overview of metadata please see the “Metadata” section of the handbook.

10/20/2015 22

Project Strategy

Before beginning a digital imaging project, a plan or strategy for completing the project efficiently and to

the best possible standards should be created. A strong strategic plan should be developed with all

parties involved in the project (i.e. information technology, legal, etc.). A digital imaging project can

prove time consuming and involve many tasks; careful planning can save an agency time and money.

Whether the project will be done in-house or contracted out to a vendor, the following should be

included in a plan:

•

•

•

•

Identifying materials

o It is important to identify all documents and objects that will be digitized. This will

allow for a better understanding of how long the project will take and whether it will be

feasible to digitize the selected material. The frequency of use should also be

considered when selecting documents for digitization.

Preparing materials before scanning

o Preparation includes, but is not limited to, sorting files and removing unnecessary

materials such as duplicate documents, removing documents from binders, removing

staples and papers clips, and conservation of deteriorating documents.

Training Staff

o Staff involved should be trained in the use of any imaging hardware or software, and

informed on the best practices for proper metadata creation.

Preserving documents

o What long-term strategy is in place for ensuring access to and preservation of digital

objects over time?

Management and Preservation of Digitized Documents

How long an agency will maintain custody of digitized documents depends on both operational needs

and the required retention period of the record. Managing and preserving electronic records requires a

systematic, sustainable, and on-going plan. Periodic checks to see that files haven’t been damaged or

altered, migration to new formats, and transfers may all be necessary. Maintenance of e-records can

be just as costly and time consuming as creating the records in the first place. Data recovery for records

that have not been maintained properly is also extremely expensive.

Teamwork is Crucial

Once digitization is complete, a thorough review of the resulting files should then occur. Once all files

are deemed acceptable by all parties, it may be time to send the hard copy files to the State Archives if

they are records that were flagged for transfer. State Archives staff members are also available for

consultation.

1

0/20/2015 23

Glossary

Access: Ability to locate, retrieve, and provide records at the appropriate time for the appropriate

individuals.

Active File: Materials which are maintained in the office of an agency for current daily operations and

are referred to frequently.

Active Record: A record which is regularly referred to and required for current use. Usually considered

to be those records that are referred to more than once per file drawer per month.

Administrative Value: Records useful for providing information related to an agency’s organizational

structure, administrative decisions, policies ,or procedures.

Administrative Records: Records that are created to help an agency accomplish its current

administrative functions.

Archival Record: Document whose long term value justifies its permanent retention.

Archival Value: The determination in appraisal that records are worthy of permanent preservation by an

archival institution.

Archives: (1) The agency responsible for selecting, preserving, and making available archival materials.

(2) The building in which an archival institution is located. (3) Those records that are no longer required

for current use but have been selected for permanent preservation because of their evidential,

informational, or historical value.

Cloud Computing: IT services (storage or software) delivered via internet technologies although based

offsite and frequently provided by a vendor.

Convenience Copy: A copy created for administrative ease of use, also called a working or reference

copy; not the official record.

Copy: The reproduction, by any method, of the complete substance of a record; a reproduction of an

original.

Cross-Reference: A notation in a file or on a list showing that a record has been stored elsewhere.

Database: A set of data, consisting of at least one data file or a group of integrated data files, usually

stored in one location and made available to several users at the same time for various applications.

Database Management System (DBMS): A software system used to access and retrieve data stored in a

database.

Data Processing: Handling and processing of information necessary to record the transactions of an

organization. Usually used in conjunction with mechanical and electronic data–handling equipment.

Digital Signature: A cryptographic technique for creating a bit stream that can be affixed to a document

(or any other digital object) and thereby attest to its authenticity. A digital signature includes a private

key that is known only to its owner and a reciprocal public key that can be made available to anyone. A

digital object signed with a private key can only be validated by its reciprocal public key.

10/20/2015 24

Electronic Record: Digital information content that is captured and stored in a computer storage device

or media for future use as evidence of business transactions that requires access to computer

technology to render it intelligible to humans. “Born digital” refers to records created in a digital format

while scanned digital records are reproductions or images of hard copy records.

Encryption: The process of systematically encoding a bit stream before transmission so that an

unauthorized party cannot decipher it.

Fiscal Value: The usefulness of records to the organization as relating to financial transactions and the

movement and expenditure of state, federal, or other funds.

Historical Value: (1) The usefulness of records for historical research concerning the agency of origin or

for information about persons, places, events, or things. (2) The value arising from exceptional age,

and/or connection with some historical event or person.

Holdings: All of the records in the custody of a given agency, organizational element, archival

establishment, or records center.

Inactive Records: Records that have a reference rate of less than one search per file drawer per month.

Records that are not needed immediately, but which must be kept for administrative, fiscal, legal,

historical, or governmental purposes, prior to disposition.

Information Governance: Is not only managing the retention and disposition of the record but the

complete management of the metadata of the record, tiering of content across storage platforms,

security classification of the content during its lifecycle, data privacy attributes of the record during its

lifecycle, and digital rights of the content.

Legal Custody: Control of access to, possession of, or responsibility for records based on specific

statutory authority, ownership, or title to documentary materials.

Legal Value: Refers to the usefulness of records that form the basis of legal actions, proof of agency

authority and/or that contain evidence of legally enforceable rights or obligations of government or

private persons.

Long-Term: A period of time long enough for there to be concern about the impacts of changing

technologies, including support for new media and data formats, and of a changing user community, on

the information being held in a repository. This period extends into the indefinite future.

Migration: A strategy for avoiding obsolescence in media or file type that involves the periodic

duplication of files and/or content into new media and/or file type, respectively.

Native File Formats: Electronic records in a native file format can only be recognized and opened by the

software application that originally was used to create the records. Sometimes an application other

than the original software application may be able to open records in a native format but key features

(line spacing, special types of fonts, and the like) may be rendered differently.

Off-Line: Not under the direct control of a computer. Refers to data on a medium, such as a magnetic

tape, not directly accessible for immediate processing by a computer.

10/20/2015 25

On-Line: Under the direct control of a computer. Refers to data on a medium, often a hard drive,

directly accessible for immediate processing by a computer.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR): A process that scans text images and stores the scanned

characters in digital form.

Permanent Record: A record considered being so valuable or unique that it is to be permanently

preserved.

Preservation Duplicate: An exact copy of a record held off site and used to preserve the record in the

event of a disaster.

Record Copy: A record that is designated to be kept for the full retention period; not a reference,

working, or convenience copy.

Records Creator: The role played by those persons or client systems that provide the information to be

preserved. This can include other archival information systems or internal persons or systems

Records Appraisal: The analysis of records with the objective of establishing retention policy.

Records Disposition: Final processing of records; either destruction, permanent retention, or archival

preservation

Reference Copy: A copy of an official record, which serves as a substitute for reference purposes. Also

called a convenience or working copy.

Temporary Records: Records that are disposable as valueless after a stated period of time.

Trustworthy Digital Repository: A trustworthy digital repository accepts responsibility for the long-term

maintenance of digital records for current and future users; has an organization system that supports

the long-term sustainability of the repository and its contents; designs and implements its systems in

such a way as to ensure on-going access to and security of digital records in its custody; establishes

credible methodologies for system evaluation that meet community expectations of trustworthiness;

and supports polices, practices and actions that can be measured and audited.

Trustworthy Records: Trustworthy electronic records are reliable and authentic records whose integrity

has been preserved over time. Reliability references that records can be trusted as an accurate

representation of the activities and facts associated with a transaction(s) because they were captured at

or near the time of the transaction. Authenticity means that electronic records are what they purport to

be.

Vital Record: Records containing information necessary to the operating of government in an

emergency created by disaster; and records to protect the rights and interests of individuals or to

establish and affirm the poser s government in the resumption of operation after a disaster.

1

0/20/2015 26